Why Functional Contextualism?

Theoretical vs. Technical Eclecticism.

As I said, coming out of grad school I had a vague idea of what I was doing and a lot of explanations and techniques. I didn’t really have any way of organizing what I was doing in sessions, and my clinical expertise, to my mind was explaining and diagnosing. I was very good at that. I actually used to teach courses on the DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual).

This article by Lazarus and Beutler helped me see what I was struggling with.

Here’s a quote:

Unsystematic eclectics and theoretical integrationists attempt to meld disparate ideas into harmonious wholes. They desire to construct a superordinate umbrella and build a coherent framework by blending the best elements from different theories. The main problem here is that, on close scrutiny even theoretical tenets that seem to be interchangeable among different theories, often turn out to be totally irreconcilable.

I was a technically eclectic therapist. Which meant throwing stuff against a wall and hoping something stuck.

I needed a framework, a theory, a ground to stand on so I could organize what was happening for me and my clients.

Why Functional Contextualism?

How does the world work? Why is this happening? What can be done?

These are philosophical questions we ask and answer without much awareness. Usually we ask this: How does the world work and why is this happening to me? The answers we make to these questions, which usually happens early in our life has a massive impact. These unexamined answers alway have a profound impact on trauma folk especially. I can talk more about that in another post.

The answers to these questions sorts the data we receive from the world and give us a framework. We predict, describe and understand our experience through the lens of these answers. These answers are called world views. If you want to do a deep dive into world view here’s a good paper. If anyone is interested we can do a deep dive conversation on this and any other resource I provide.

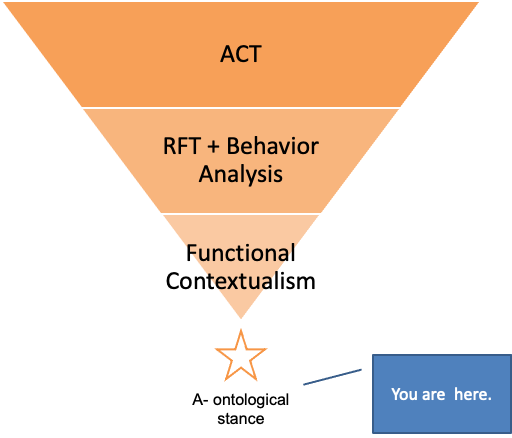

When I was beginning as an ACT therapist I didn’t grasp that ACT answers these questions in a profoundly weird way. Here’s a graphic to make it clearer.

The absolute weirdness of this world view is the a-ontological stance. So what does that actually mean for us working clinicians?

It means that all of the “things” we learned about in graduate school Those things that caused problems–thought distortions, attachment disorders, neuroses, ect. Don’t actually exist and do not have causal status. WHAT!?!?! That there are no immutable solid aspects of our experience and the answer from this stance to any clinical question is “It depends.” That nothing is solid and permanent, everything can change.

Ok. Sort of. In my mind there is clarity and stability. I see this in behavioral principles. These principles are like physics to me.

Here’s the short version: Behavior that we see more of is reinforced. Behavior that is unstable or absent is punished. We can only tell if something we are doing is a reinforcer or punisher by observing the behavior. There are no Reinforcers or Punishers outside of a particular context. Which is always changing. I know, it doesn’t sound that much clearer. We will keep talking about it in later posts.

So why would I as a working clinician who doesn’t have the time to learn stuff that doesn’t immediately help me do my job learn all of this geeky stuff?

Because asking myself, “How does this crazy/annoying/frightening thing my client is doing make perfect sense?” allows me to do things clinically that I didn’t think were possible.

Circling back to functional contextualism–when I start from the assumption that my client isn’t broken, that pain isn’t a problem and that what I’m seeing has to make sense and all I have to do is figure out how the therapy relationship is transformed.

Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing, there is a field. I'll meet you there.

Rumi

Obrigado Vitor.

Uma leitura impressionantemente agradável.